Founding

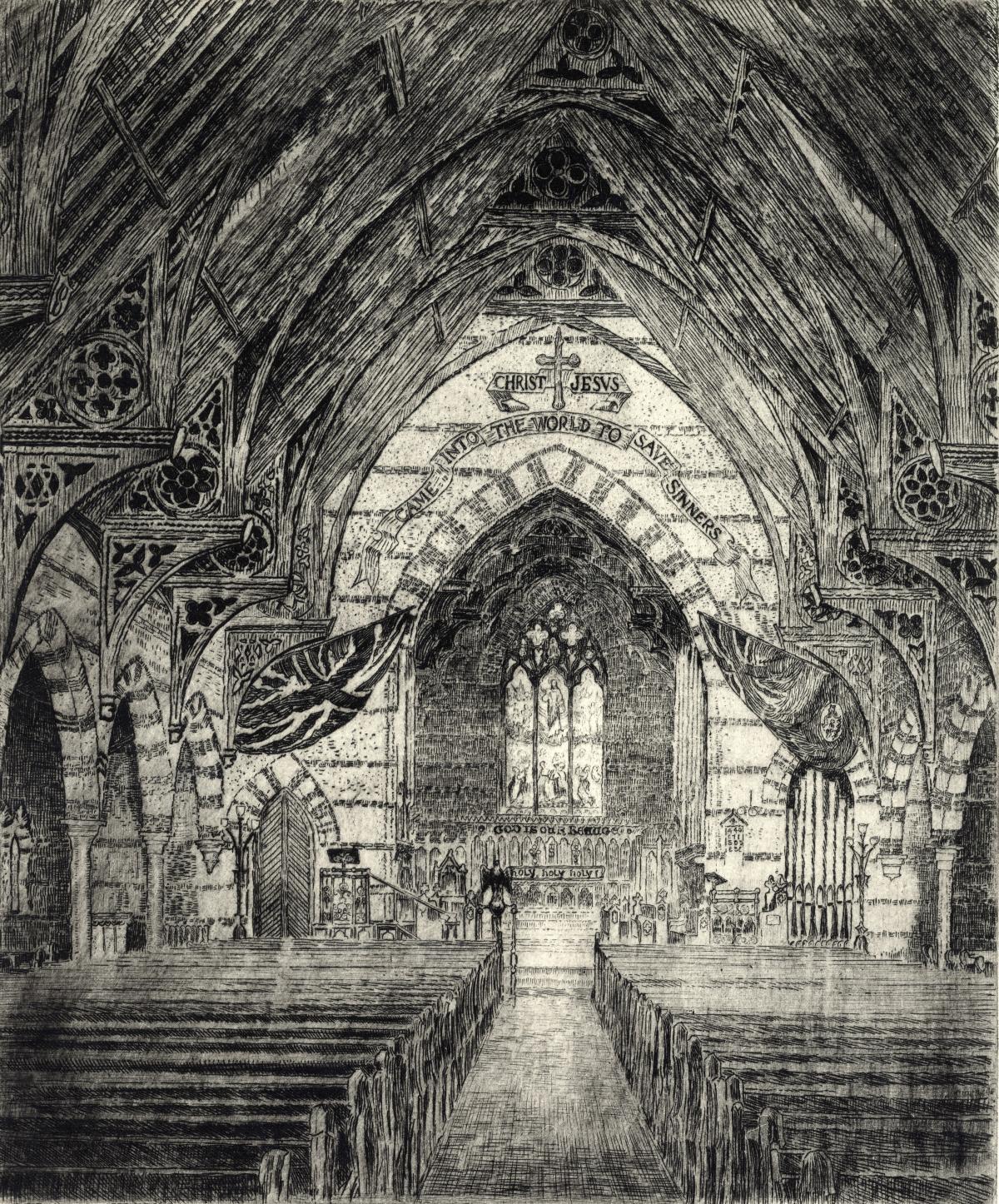

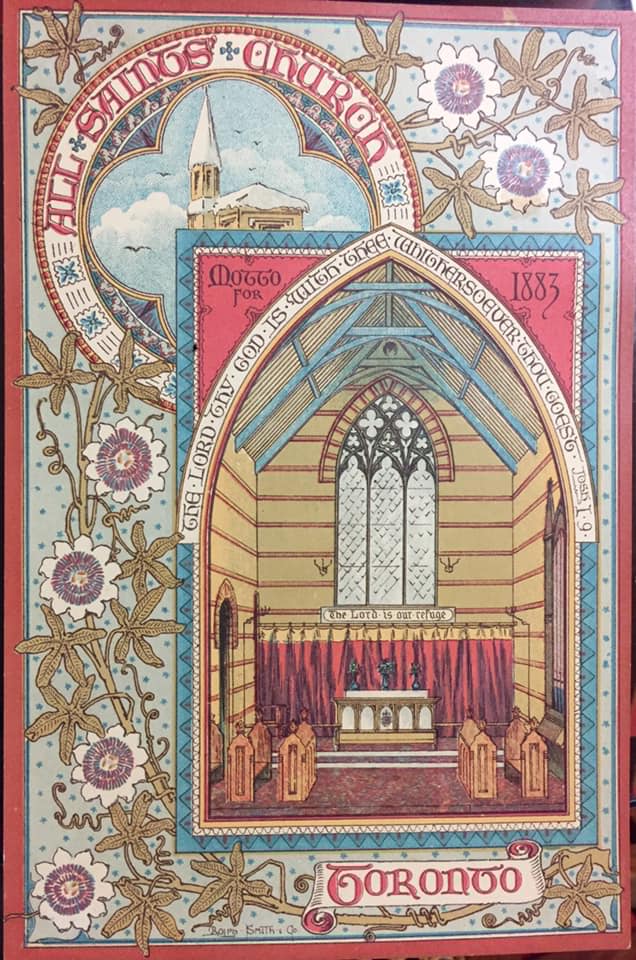

Established in 1872, All Saints attracted “a congregation of various classes” from the start. Its first rector, The Reverend Canon Arthur Baldwin, was known to provide for people in need and chaired the Diocesan Widows’ and Orphans’ Committee. The church building, completed in 1874, reflects the generosity and wealth of All Saints’ founders. All Saints has been called “this nation’s perfect Gothic Revival realization of the synthesis of architecture and applied art.”

As the city’s population expanded, so did All Saints’ congregation. Even with a capacity of 800 and two main Sunday services, the church was frequently filled to overflowing. The church began a vital women’s ministry, with deaconesses playing a significant role. They functioned as private health visitors and public health advocates, communicating the concerns of the poor and immigrant to the rich and established.

After the First World War, families began moving out of the neighbourhood. This exodus accelerated after the Second World War. Mansions became boarding houses, and area residents were increasingly poor and transient.

Renewal

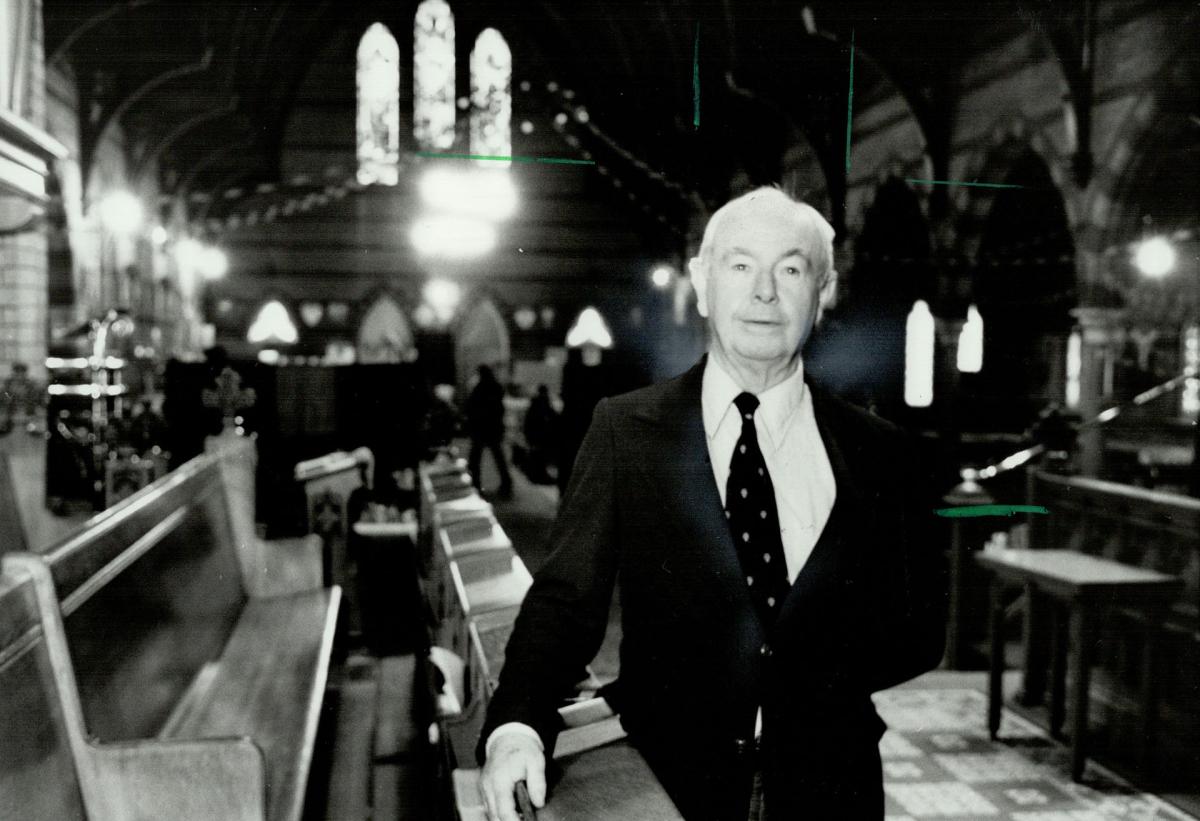

In 1964, All Saints hired a new rector named Norman Ellis. Within a few years, he built up the congregation by connecting with residents in neighbouring Moss Park as well as men staying in nearby shelters. However, these new parishioners couldn’t support the church financially in the way earlier generations had.

Ellis found new ways to respond to the neighbourhood’s increasing needs. In 1970, All Saints turned its parish hall over to the Friendship Centre, a men’s club that offered coffee, sandwiches, TV, and card games for men staying in nearby shelters. The same year, the Queen Street Mental Hospital launched the Dundas Day Clinic in the church hall to provide counselling for outpatients. All Saints was becoming a community hub.

Along with a group of advisors, Ellis proposed that, rather than remain a traditional parish church, All Saints become a “church-community centre,” managed by a board of directors. On March 1, 1971, the Bishop and Synod of Toronto accepted such a resolution. All Saints became, in Ellis’ words, “a People’s Place for rest and refreshment, for peace and reconciliation, welcoming the lonely, the homeless, the unloved.”

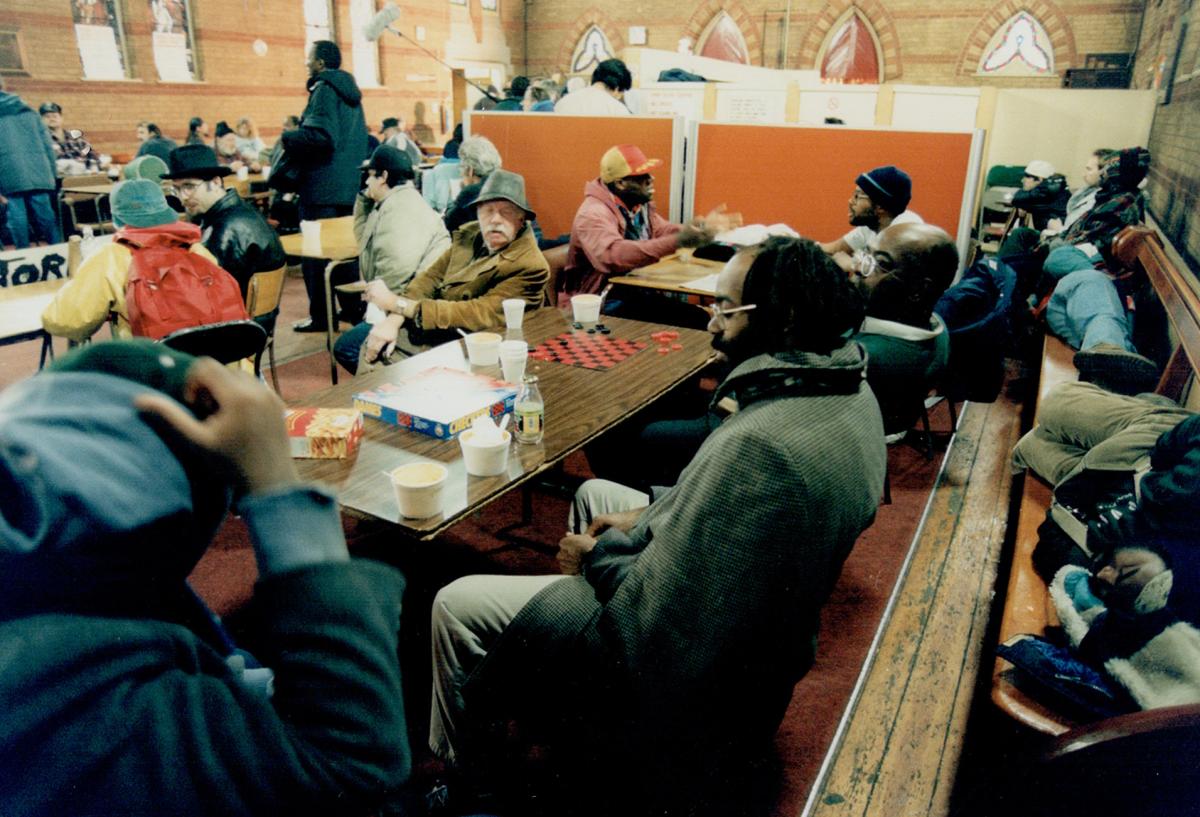

Most of the church’s pews were removed to create space for the Open Door Centre, a women’s drop-in that opened in February 1972. The Open Door and Friendship Centres soon opened to men and women alike. Ellis called these drop-in centres “parlour space,” as they provided places for rooming house residents to meet their friends. The drop-ins provided snacks and light meals, telephone access, a mail service, a room registry, low-cost clothing, and various recreational and counselling services.

Most of the church’s pews were removed to create space for the Open Door Centre, a women’s drop-in that opened in February 1972. The Open Door and Friendship Centres soon opened to men and women alike. Ellis called these drop-in centres “parlour space,” as they provided places for rooming house residents to meet their friends. The drop-ins provided snacks and light meals, telephone access, a mail service, a room registry, low-cost clothing, and various recreational and counselling services.

Worship remained a vital part of All Saints. For Ellis, the heart of ministry was friendship. He began holding weekly Agape Suppers, bringing individuals and families together in the parish hall for a fellowship meal followed by Bible study. Whether people attended worship or not, he considered everyone who came to All Saints to be part of the Church. “The Church,” he wrote in 1974, “is not buildings or the institution but people, and will be where people are, where people live, where they spend their time, work, and play—at the place of meeting. For Jesus was so obviously in the world.” All Saints began hosting legal clinics, counselling for psychiatric survivors, health clinics, and support for First Nations people. Over the years, several non-profit groups were based at All Saints, including Council Fire, Operation Springboard, Street Health, Homes First, and OCAP. All Saints became a community hub dedicated to grassroots anti-poverty work and community organizing, helping pioneer new approaches to health such as harm reduction.

Today

All Saints remains a “People’s Place” where people in need can find rest and refreshment, and share in community. The Open Door Centre is now the All Saints Drop-in, and is overseen by the All Saints Church-Community Centre Board of Management.

All Saints continues Norman Ellis’ vision of ministry as friendship. Every person who walks through the church doors is accorded acceptance, dignity, and respect. The worshipping congregation remains true to the vision of the church’s founders, welcoming people from all walks of life. All are welcome to join and share in God’s love at Dundas and Sherbourne.

Further Reading

Commemorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of All Saints Church Toronto 1872—1922. https://archive.org/details/fiftiethannivers00allsuoft

Ellis, Norman. My Parish is Revolting. Hodder and Stoughton, 1974.

McHugh, Patricia and Alex Bozikovic. Toronto Architecture: A City Guide. McClelland and Stewart, 2017. https://www.google.ca/books/edition/Toronto_Architecture/tzTWDAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Palmer, Bryan D. And Gaétan Héroux. Toronto’s Poor: A Rebellious History. Between the Lines, 2016.

Robertson, John Ross. Sketches of Toronto Churches. J. Ross Robertson, 1886. https://www.google.ca/books/edition/Sketches_of_Toronto_Churches/chc1AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Incumbents / Priest-Directors of All Saints

1872-1908: The Rev’d Canon Arthur Baldwin

1909–1918: The Rev’d Walter J. Southam

1918-1949: The Rev’d Thomas W. Murphy

1949-1953: The Rev’d Benjamin Smyth

1953-1963: The Rev’d John McKibbon

1964-1982: The Rev’d A. Norman Ellis

1982-1990: The Rev’d Canon Bradley Lennon

1990-1996: The Rev’d Michael Marshall

1996-2009: The Rev’d Canon Elizabeth Jean Loughrey

2010-2017: The Rev’d David Opheim

2018-Present: The Rev’d Dr. Alison Falby